Alzheimer’s Disease and Single-Cell Transcriptomics: Why Cell-Level Views Matter

Nuhash Gazi

•

Nuhash Gazi

•

Introduction

In my opinion, Alzheimer’s disease represents one of the greatest health challenges of this century. Millions of people suffer from progressive memory loss, impaired cognition, and eventual loss of independence. Despite extensive research, there are no curative treatments, and most available therapies only slow decline. This frustrating reality tells us that we still do not fully understand what is happening inside the diseased brain.

Background on Alzheimer’s Disease and Its Challenges

Alzheimer’s disease is defined by hallmark pathologies such as amyloid-beta plaques, tau tangles, and progressive neuronal death. These features disrupt brain communication and lead to the gradual loss of memory and daily function. Traditional treatment approaches have largely focused on these hallmarks. However, drugs that reduce amyloid burden or target tau have shown limited benefits in clinical trials. This underlines the complexity of the disease and suggests that simply removing plaques or tangles is not enough.

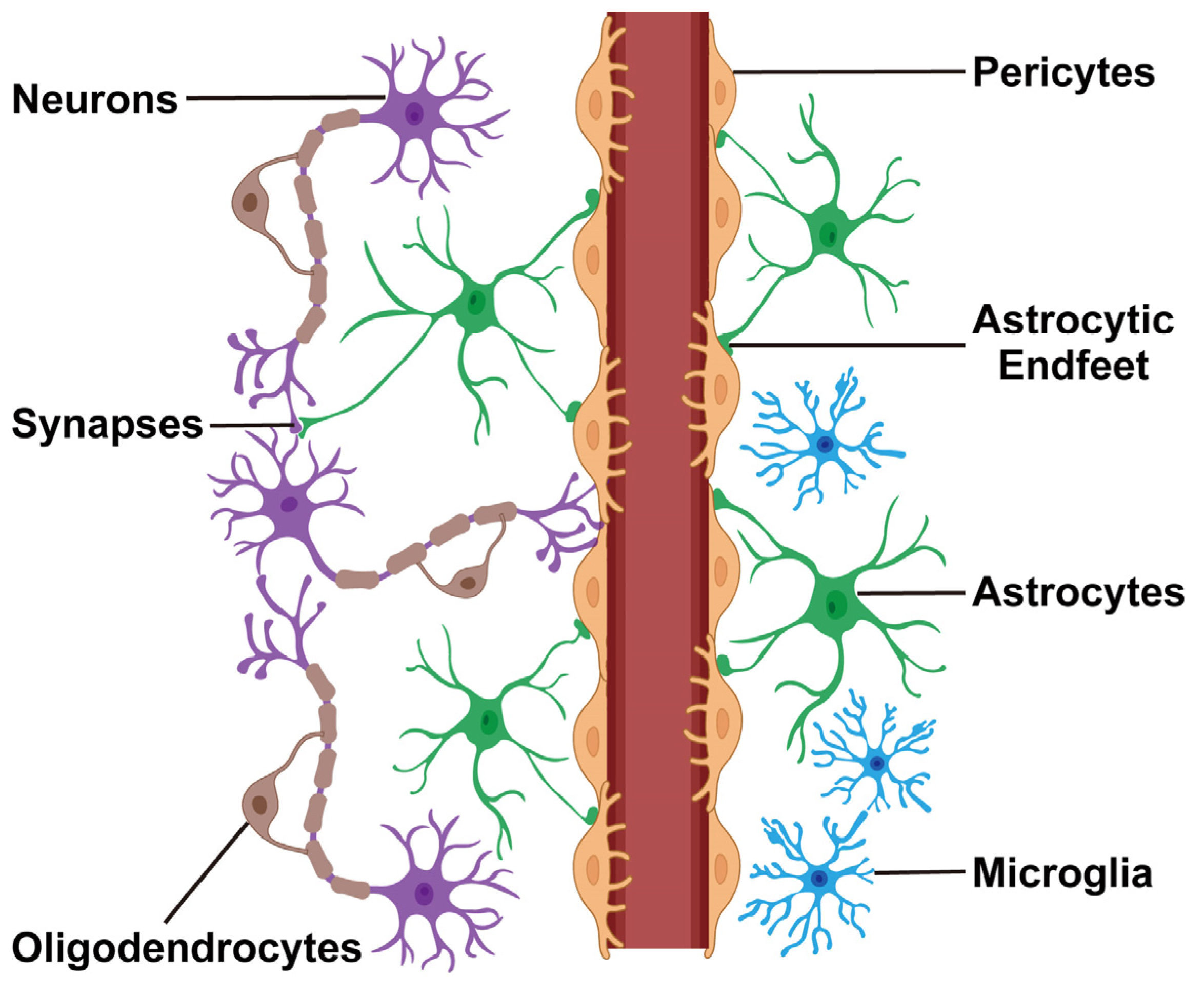

The human brain is composed of many different cell types, including neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia. Each cell type contributes differently to brain function and responds differently to stress or injury. Conventional research methods often average signals across many cells, which hides this natural diversity.

From my perspective, this lack of cellular resolution is one of the main reasons why previous therapeutic strategies have not achieved the expected success. When we blur many cell types together, we miss the specific cells that are most vulnerable or most protective. A deeper, cell-level view is necessary to uncover the true mechanisms of the disease.

What Is Single-Cell Transcriptomics?

Single-cell transcriptomics refers to techniques that measure gene expression in individual cells. Methods such as single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) allow researchers to capture the transcriptome of thousands of single cells simultaneously. Instead of producing a single, averaged profile of a tissue, these methods produce a separate profile for each cell.

Compared to bulk transcriptomics, which merges signals from many cells, single-cell methods reveal hidden diversity and rare populations that may play critical roles in disease. In Alzheimer’s research, this ability is especially valuable because the disease does not affect all cells equally. Certain neuron types are more vulnerable to degeneration, and glial cells can adopt disease-specific states that either worsen or protect against pathology.

By distinguishing these differences, single-cell transcriptomics provides a more complete and accurate view of disease processes. It allows us to ask very specific questions: Which neuron subtype degenerates first? Which microglial state is harmful and which is protective? Which astrocytes support resilience against cognitive decline?

In my view, this move from “average brain tissue” to “individual cells” marks a conceptual shift in Alzheimer’s research. It opens the door to truly understanding the cellular players behind memory loss and introduces the foundation for more precise therapies, which I will explore further in the next posts of this series.

In my opinion, Alzheimer’s disease represents one of the greatest health challenges of this century. Millions of people suffer from progressive memory loss, impaired cognition, and eventual loss of independence. Despite extensive research, there are no curative treatments, and most available therapies only slow decline. This frustrating reality tells us that we still do not fully understand what is happening inside the diseased brain.

Background on Alzheimer’s Disease and Its Challenges

Alzheimer’s disease is defined by hallmark pathologies such as amyloid-beta plaques, tau tangles, and progressive neuronal death. These features disrupt brain communication and lead to the gradual loss of memory and daily function. Traditional treatment approaches have largely focused on these hallmarks. However, drugs that reduce amyloid burden or target tau have shown limited benefits in clinical trials. This underlines the complexity of the disease and suggests that simply removing plaques or tangles is not enough.

The human brain is composed of many different cell types, including neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia. Each cell type contributes differently to brain function and responds differently to stress or injury. Conventional research methods often average signals across many cells, which hides this natural diversity.

From my perspective, this lack of cellular resolution is one of the main reasons why previous therapeutic strategies have not achieved the expected success. When we blur many cell types together, we miss the specific cells that are most vulnerable or most protective. A deeper, cell-level view is necessary to uncover the true mechanisms of the disease.

What Is Single-Cell Transcriptomics?

Single-cell transcriptomics refers to techniques that measure gene expression in individual cells. Methods such as single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) allow researchers to capture the transcriptome of thousands of single cells simultaneously. Instead of producing a single, averaged profile of a tissue, these methods produce a separate profile for each cell.

Compared to bulk transcriptomics, which merges signals from many cells, single-cell methods reveal hidden diversity and rare populations that may play critical roles in disease. In Alzheimer’s research, this ability is especially valuable because the disease does not affect all cells equally. Certain neuron types are more vulnerable to degeneration, and glial cells can adopt disease-specific states that either worsen or protect against pathology.

By distinguishing these differences, single-cell transcriptomics provides a more complete and accurate view of disease processes. It allows us to ask very specific questions: Which neuron subtype degenerates first? Which microglial state is harmful and which is protective? Which astrocytes support resilience against cognitive decline?

In my view, this move from “average brain tissue” to “individual cells” marks a conceptual shift in Alzheimer’s research. It opens the door to truly understanding the cellular players behind memory loss and introduces the foundation for more precise therapies, which I will explore further in the next posts of this series.